Q: Darlingtonia: the cobra lily

A: The genus Darlingtonia contains only one species,

Darlingtonia californica Torr. It is a pitfall pitcher plant related to

Sarracenia and Heliamphora. It is remarkable because of the pair of

appendages that are either described as fangs or a moustache, depending upon the details of the brain of the one

making the description.

Like all pitfall traps, this plant has no moving parts. However, it is still marvelously effective. It attracts prey by

its colorful leaves that emit a honeylike scent. Prey land on the pitcher top or the fangs to feed on nectar. It is exuded in

glistening abundance on the fangs, and as the insects forage they eventually crawl upwards towards the pitcher mouth.

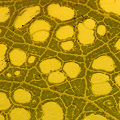

Since the pitcher top is set with countless glassy windows, light illuminates its interior and makes it so

very appealing. Once insects enter the pitcher, they are in serious trouble because the escape route is hard to find. Meanwhile,

the pitcher tube downwards is very easy to find, indeed! (As Sir David Attenborough would say.) The pitcher tube is slick and adorned with downwards-pointing hairs. The prey

plummet downwards and to its doom. The pitcher base is filled with fluid. No digestive enzymes have been detected

in this plant; it apparently relies upon bacteria and commensals

to do its digestion for it.

Notice that there are significant elements of the lobster-pot trap in how Darlingtonia

captures its prey. It is more than just a pitfall trap.

The commensals in Darlingtonia

deserve special comment because they are so horrifying. The most obvious are the

larval form of a flying midge (Metriocnemus edwardsi). These are small (about 1 cm long) white

wormlike creatures.

Cut open a Darlingtonia pitcher and you will see swarms of them gobbling up

the prey that are submerged in the pitcher fluid. It is truly horrible to behold. Oddly, looking at

these creatures made me decide that

Roridula was carnivorous---see more about that in the Roridula

section of the FAQ.

Another organism in Darlingtonia that truly depends upon the plant to live is a tiny creature called

Sarraceniopus darlingtoniae. This has the unfortunate common name of "slime mite."

Sarraceniopus adults

live the whole summer and winter in pitchers, feeding upon bacteria. When the old pitchers decay in the spring, bands of

Sarraceniopus

climb out and gather near the newly forming pitchers' mouths. As soon as the pitchers open, the

Sarraceniopus climb in and take up residence. Isn't that cute? And if that's not interesting

enough for you, try this one--Sarraceniopus females are arrhenotokous, meaning that if they are

unfertilized they give birth to

offspring that are all males. That, my friend, is strange!

It may astonish you, but even though this is a well known, dramatic plant, there is some uncertainty as to

what pollinates it! You would think it would be easy to just sit by the

plant and see who visits the flowers. But people have done just this, day and night, and still pollinators have never been observed

visiting the flowers in a consistent way. Some researchers think it may be

spider pollinated. However, I've observed the plants being pollinated by burrowing bees

(Andrena nigrihirta) and my observations are described in McPherson & Schnell (2011).

The most frequently used common names for Darlingtonia are cobra lily and

California pitcher plant. I have read they are called deer licks, but have never heard this in use.

The Latin name was chosen by the discoverer of the plant, William Dunlop Brackenridge, to

honor his chum the Pennsylvanian botanist William Darlington. Actually, I am sure that Native Americans had their own names

for this

plant, but I have not yet discovered them. Since we are talking about history, I must mention that the old story--that Brackenridge

discovered the plants while being pursued by Native Americans--is a bogus bit of urban legend.

In 1891 the name

Chrysamphora was established for this plant, but later overturned by the botanical Powers That Be,

because it was superfluous.

Page citations: Fashing, N.J. 2004;

Freeman, L. 1996; Hepburn, et al. 1920; McPherson & Schnell 2011; Rice, B.A. 2006a;

Nyoka, S., and Ferguson, C. 1999; Rondeau, J.H. 1991; personal observations.